A book I thought about eating, but couldn't

Or, try your best not to eat the books your friends lend you (or, I love zines but sometimes read books too)

Yesterday at a café I spotted a zine pinned to a corkboard by the bathroom, titled The story of a balding hulking wrestler crying on the toilet. It begins: “as I write this, I sit on a toilet in the bathroom of a hotel in New York City. My boss is on the other side of the door. We’ve been doing cocaine for 48 hours straight, trying to finish this movie.” Reader, I pocketed that zine instantly. Who wouldn’t?

Back at home, two iced lattes and one epic shit later, I shelved it in our zine library, right next to NEXT GENERATION WOMBEN: What Our Bodies Are For, and the Plan to Steal Yours by Some Freaky Transsexual. More authors should be writing sentences like “I LIVE for your moral panic. I CRAVE IT. If given the chance, I will gobble up the opportunity to plunge my own hand into a cis woman’s cadaver, pull that uterus out (vaginal cuff and all), and stuff it into my body like Halloween candy.” Why doesn’t more weird writing make it into print? This is a serious question.

Even if you’re an acclaimed writer, it’s hard to compete with the rawness, strangeness, and off-kilter humor that zines deliver time and again. (The problem with literary publishing today is that no one is releasing books with titles like OF COURSE I’d still love you if you were a worm but like we might have to renegotiate certain aspects of our relationship, y’know? It’s a big adjustment. (A guide to safely and responsibly loving your partner post wormification).) Another way of saying this is that in a landscape of capital-A Art that is nice but perhaps a little boring, zines are reliably interesting. Zines do not care if they are good. They do not care if they garner positive critical reception. They do care about grabbing your attention, and then grabbing your heart. (Some zines might even try to grab your womb). Eventually they will probably leave you standing on a Soapbox Lovingly Lecturing About Zines.1

The best literary writing (or rather the literary writing I’m most interested in) shares some of the qualities inherent in self-published material; its strangeness survives the gatekeeping and formalities of the publishing process. The best literary writing WANTS YOUR ESSENTIAL ORGANS and IS COMING FOR THEM.

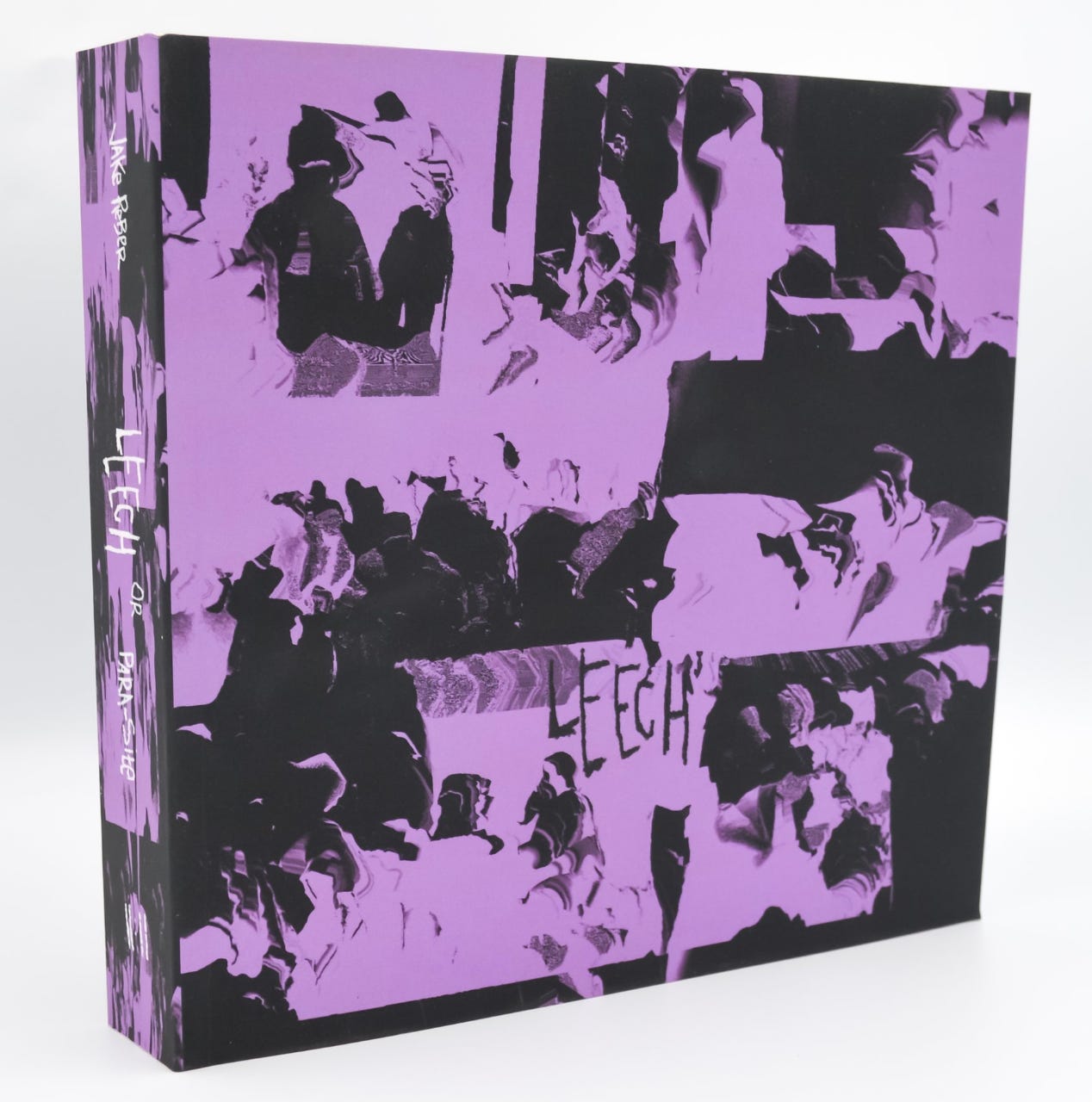

That’s more or less how I felt about Jake Reber’s LEECH or PARA-SITE, published recently by 11:11 press. It’s as good as a balding hulking wrestler crying on the toilet. If you are interested in the Taylor Swift-Simone Weil-Cixous abjectional axis of flesh, in smelling like the mall, in indexical excess, in static, in low-budget mysticism, in how all texts are essentially assemblages or distortions or photocopies of other texts—LEECH might be for you. If LEECH was about just one thing, it’s about how writing is a parasite of reading. In print or online, the act and experience of reading is an everyday miracle; Reber reminds us that the transcendence of the written word is linked to the ways in which it is visceral and hungry, a little bloodsucker.

I usually read in the mornings, because I do not like mornings and reading makes them less painful. I started on LEECH one morning, intending to read a bit before going about the day, but snarfed it the way I snarf a bag of potato chips while watching something absolutely gripping like a documentary about Pez collecting. LEECH is the perfect thing to read while you should be doing something else.

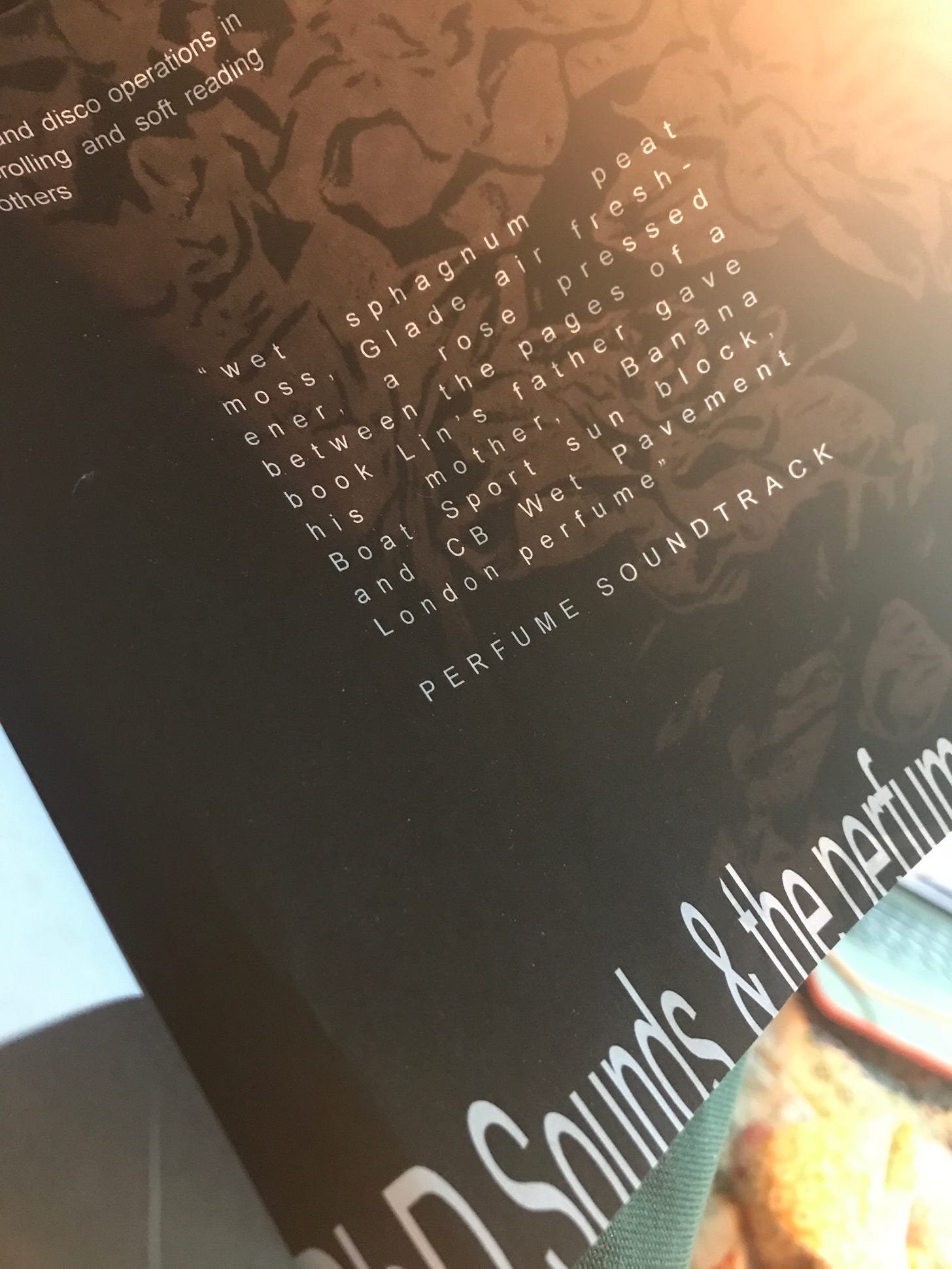

When I landed at a spread about “the perfume of reading,” a reference to Tan Lin’s Bibliographic Sound Track (2012), I could smell each element of the bookish perfume, but especially the Banana Boat Sport sun block, which my grandmother would wear when she took us swimming to the kinds of Minnesota and Wisconsin lakes where it was occasionally a good idea to check for leeches in the water. As an imaginary sharp fake banana scent invaded my nostrils, along with the accompanying dankishness of remembered lake water, I was acutely aware of the shape and weight of the book/chunk in my hands. LEECH is a meaty little handheld slab of pages, and would be excellent smothered in some kind of barbecue sauce and stuffed into a sandwich.

Unfortunately the copy of LEECH I was reading had been lent to me by a friend. While Danika (a brilliant poet) is generally supportive of my bookeating tendencies, she had informed me that I absolutely. could. not. eat. her copy of LEECH because it cost $45. So, fighting my urge to nibble on LEECH (or at a bare minimum, lick it), I continued to read, appreciating how each leaf was just transparent enough to hint at the black and white graphics on its reverse. This means that each page in the book is somehow also the page after it, that there is a slice of attention suspended between one spread and the next. (Actually, this is the case for every book—while texts have pages, books do not have pages, only leaves—it just takes a lot to make the reader aware that while the page is imaginary, the book is real).

Passages in LEECH are reminiscent of Raphael Rubenstein’s The Miraculous, both in the ways the book charts the known universe of performance art, and how descriptions of performances and other conceptual artworks are intentionally sequenced into something that is both a narrative and a catalog.

After reading, I had a hunch that much of LEECH’s curb appeal was due to Mike Corrao, who is the kind of rogue designer-poet that can make even very bad type look very good. I was curious about what kind of manuscript Mike had received from the writer, since at points in LEECH Reber references PowerPoint’s value as a compositional tool: “converting everything into/ powerpoint does/something to your brain & / I’m sure its not great. / However, the limitations/and constraints on design / & aesthetics produce / necessary disasters.” Mike: “some of the images themselves are made using a distortion tool that was, I think, specific to one version of PowerPoint.” Mike pushed the book’s contrast, eliminating many of the gray midtones and blips of color in the original manuscript (“especially with print on demand services it’s hard to make color look good in a book”), giving the final book a stark, elegant, black-and-white cohesion that feels a little haunting. A hefty but portable volume, LEECH has the gravity and presence of a worn Bible, or maybe a prayer book for the end of times.2 Below a framed piece of glitch art, the last page references Simone Weil: “I sit in the garden w/ unmixed attention — a prayer.”

as half of late night copies press: yes, I am obligated to wax poetic about self-publishing on a regular basis

while it may seem odd to review a book in terms of its volume … I’ve written before about how volume can become a literary reference. More writers should be thinking about the shape, size, and specific weight of their books.